New projections predict a bleak future for the teaching profession in sub-Saharan Africa. It’s time for the international community to invest in the region’s teachers, starting with the G7.

By 2030 less than half of Africa’s primary and lower-secondary teachers will have the training they need to do their jobs. That’s according to new projections released today by the Atlantis Group, an elite group of former ministers of education and heads of government supported by the Varkey Foundation.

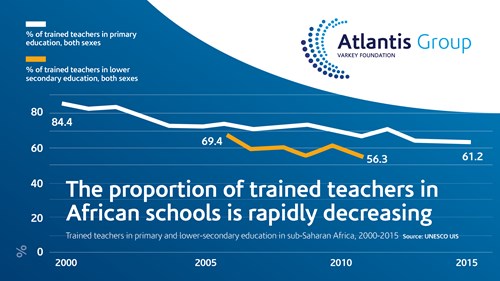

A review of international education data published by the UNESCO Institute for Statistics shows that the proportion of trained primary and lower-secondary teachers in sub-Saharan Africa has declined rapidly since the turn of the century, even as governments have brought thousands more educators into schools.

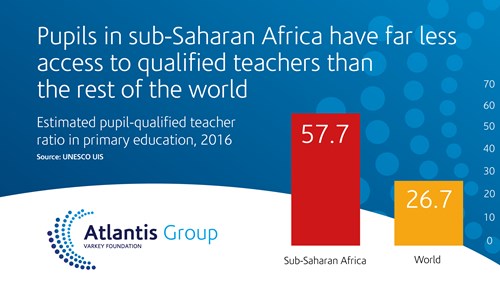

In primary schools, the percentage of trained teachers has fallen by 27.5% in just 15 years, from 84.4% in 2000 to 61.23% in 2015. In lower-secondary schools, the percentage of trained teachers fell by 18.8% in the six years for which data is available, from 69.4% in 2006 to 56.3% in 2011. The estimated ratio of pupils to qualified primary teachers in the region also remains over twice the global average (57.7 to 26.7).

If this trend continues, the Atlantis Group estimates that by 2030 less than half of primary and lower-secondary teachers in sub-Saharan Africa will meet at least the minimum of organized teacher-training requirements.

That would spell disaster for pupils in the region, which is already home to over half of the world’s out-of-school children of primary school age and where 202 million children currently aren’t meeting the minimum proficiencies for reading and mathematics. Without international assistance, it will also be next to impossible for many African States to recruit and adequately train the 17 million more teachers UNESCO estimates will be needed across the region in the next 12 years.

The findings should raise significant concerns about how the international community has managed the drive to deliver global universal education by 2030. Since the turn of the century, donor countries and multi-lateral institutions have spent billions of dollars to bolster universal basic education in sub-Saharan Africa. In broadly that same period, the proportion of adequately trained primary teachers has dropped by over a quarter and looks set to continue to fall.

To avoid a catastrophic collapse in the numbers of trained teachers in sub-Saharan Africa, international donors must be prepared to review their funding strategies and scrutinize the scope of their technical assistance. The Atlantis Group is calling for concerted leadership on this issue from the G7, which meets later this week in Quebec and whose members include leading aid contributors to African education.

To reverse the slide, the international community should first look to bolster funding levels for education in sub-Saharan Africa, which has increasingly lost out even as education’s share of global aid has begun to grow. The region’s share of aid to basic education, for example, has plummeted over the past seven years from over half to just 24% in 2016.

Donor governments should also be prepared to commit to sustained funding levels. Education aid may have reached an all-time high in 2016, but what is needed to deliver generational change is stable and consistent funding across a number of years – rather than a windfall one year and a drought the next.

As former ministers, members of the Atlantis Group urge G7 members to consider measures to ensure continuity, including enshrining in law a binding commitment to education investment and assistance as a percentage of their country’s GDP.

Governments must also be prepared to invest in the quality of the teaching profession itself. In particular, policy-makers should consider expanding economic support and technical assistance for teacher-training programmes, currently estimated to make up just 2% of total OECD disbursements for education. In this respect, expanded support for initial teacher training programmes is critical.

Donor countries and multi-lateral institutions cannot afford to spend billions more dollars on education in Africa over the next decade only to see the quality of teaching continue to decline. Without action, the prognosis for the teaching profession in the region is dire. By 2030, millions more children will be in African schools, but the majority will be taught by teachers whose training is so poor that it simply doesn’t register on the international scale.

The international community can still achieve its global education goal, but a significant course-correction is needed. Governments must work to reinforce initial teacher training and thus equip teachers in sub-Saharan Africa with the knowledge, skills and competencies they require to do their job, or the world risks a spiralling educational crisis that threatens the next generation.