BUSINESS IS booming. By 2020, the global market for educational technology will be worth upwards of $250 billion according the organizers of EdTechXGlobal, a major technology summit. Half of all EdTech revenue is still concentrated in the US, but mobile phones are also driving growth in traditionally offline education systems.[1] By all rights, ICT should be poised to transform education, the same way that it has almost every other aspect of our global society.

So why has tech had such a minimal impact on education? Research into hardware and software-based learning interventions has found that most have had either no impact, or a largely negative impact, on student learning.[2] Even countries which have invested heavily in ICT for education have seen only negligible gains, according to separate research by the OECD, a group of mostly rich countries.[3] National education systems are proving to be stubbornly resistant to educational technology. One academic who spoke to the Atlantis Group summed up the general frustration: “Tech has captured our imagination for over 100 years. So why is it so difficult?”

It’s clear that EdTech can work. There are success stories in classrooms, districts and regions around the world. But at a national level, tech just isn’t moving the metre on learning by any measure that matters, from reading and writing to maths and science. And when educational technology doesn’t work properly, it can cause major problems. One World Bank study that looked at EdTech policymaking found that botched tech adoption can disrupt teaching, take up too much of teachers’ time, and raise data-privacy concerns.[4] It is also enormously expensive.

What’s going wrong? Researchers talk about a lack of independent evidence, which means it’s hard to know which technology, applications, and systems are effective and which aren’t. Developers talk about heavily localized procurement, which means that it’s difficult to scale-up successful tech – or to make a profit. And teachers are often enthusiastic about tech, but are let down by an inadequate system or by their own lack of training.

All of these issues are political, rather than technological. The answers won’t come from putting more tech in classrooms. They will come from better policymaking. Governments need to coherently integrate technology into the process of learning. To do that, policymakers should look to their country’s classrooms. They should speak to teachers and school leaders about their needs. They should think about the educational changes that they want to see. And then they should consider exactly which learning technologies can help to deliver these changes.

Solid data is the foundation of good policymaking. But with EdTech that data often just doesn’t exist. Most developers will never have a chance to test their products at anywhere near the scale needed to establish their true efficacy. The schools and local authorities that purchase EdTech have little to no independent information on the products they buy. Few products face the scrutiny of independent randomized control testing, or other trials based around good qualitative research.

Such scrutiny is important. Where independent trials have been conducted, they have painted a mixed picture of the efficacy of even some of the most popular and widely available products. One expert who spoke to the Atlantis Group oversees randomized control trials of EdTech. She described the results of one damning study on a popular maths game:

“[The product] claims to make learning easy. But it removes all the hard part of the task – it’s too easy. No matter how long children play the game, they get nothing out of it.”

It’s clear that many products do work. Most experts who spoke to the Atlantis Group could point to examples of effective EdTech in schools today, or promising new products coming onto the market. The World Bank has also pointed to a number of success stories, amid mixed results on learning outcomes for EdTech overall.[5] However, the lack of independent evidence about technology has also fostered a climate of cynicism. As one expert reflected:

“There is a lot of reaction against for-profit EdTech companies among academia. Not all of them are selling snake oil.”

Today’s EdTech cannot automate learning. But it can make good teachers better. It can inform their decisions in the classroom, through more systematic data about their students’ performance and behaviours. It can help teachers make learning engaging, interactive and innovative. It can help to open new perspectives and illustrate concepts in a better way. It can also help cut down on teachers’ often onerous administrative work. And technology can also make learning more accessible for disabled or special needs learners. As one Atlantis Group member reflected: “This variety is not new to EdTech, it’s something that good teachers have always done – but EdTech facilitates this.”

Education ministers can help schools to sort the good technology from the bad. One way would be to establish a national commission on EdTech, mandated to gather independent evidence about technology in schools. Such a commission could work to establish a body of research about whether learning technologies are living up to their claims.

To be effective, such a commission needs direction. Ministers should be clear about the impact that they’re looking for. A new technology, for example, may not move the needle on standardized exams if it also takes time away from memorization and teaching to the test. But it may enhance skills not assessed at the national level such as critical thinking, collaboration and computational thinking. The question for the minister is, what’s the change that they want to see?

There are also a range of steps that education ministries can take to support teachers and school leaders. Peer-to-peer learning networks can help schools to learn from each other’s successes – and mistakes. Governments can also help to foster an evidence base around EdTech, drawing from users themselves. A review of effective approaches by the Omidyar Network, a philanthropic investment firm, has suggested that governments publish a catalogue of effective products and services, for example by drawing from user-generated reviews.[6]

Such moves would not be particularly costly, weighed against the cost of schools buying useless tech. But they would be a clear signal that central government is taking technology’s potential for education seriously. In the short term, such action would steer schools and developers alike over what really works in a particular country and why.

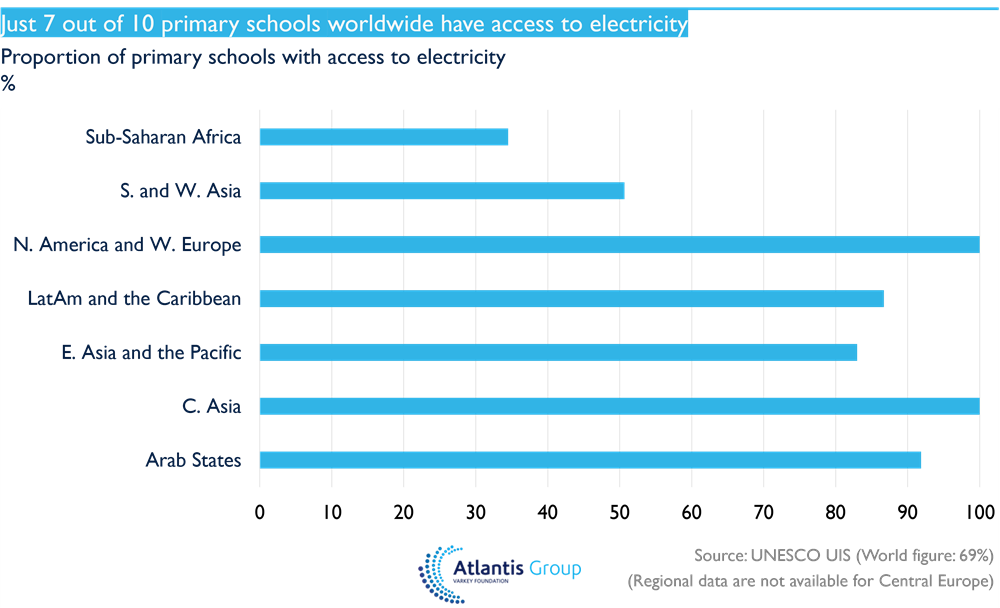

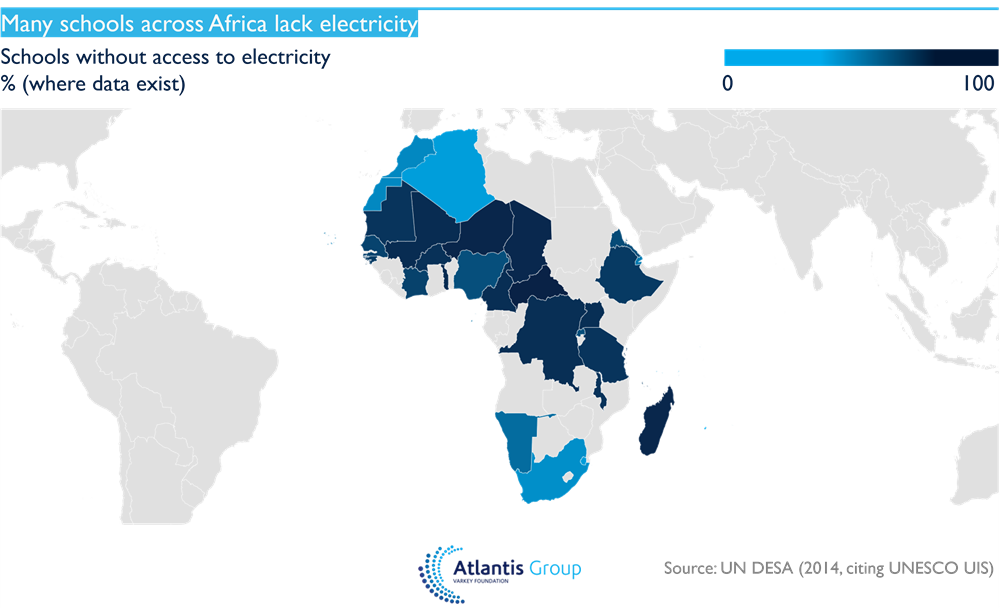

A product that works well in one place may not work at all in another. Infrastructure, including access to mains electricity and the internet, is often a key barrier to EdTech’s success at scale in low and middle-income countries. The issue is widespread. Roughly four out of every five schools in African countries lack access to electricity, along with almost three-quarters of village schools in India, according to data from UNESCO.[7]

Particularly hard served are education systems with poor access to the high-speed internet and cloud solutions demanded by today’s more advanced learning technologies. As one expert told the Atlantis Group: “Most EdTech companies think it’s fine to use cloud-computing, but in many schools around the world the basic connectivity doesn’t exist.”

Faced with these limits, some education systems are developing workarounds. Solar-powered technology, for example, can help schools cut off from the electrical grid. In many low-income countries, tech adoption is being driven by mobile phones rather than desktops or specially built hardware. Global Teacher Prize Winner Peter Tabichi, for example, regularly uses his mobile phone as a teaching tool in his school in rural Kenya. Speaking to the Varkey Foundation for this report, he said: “the moment I introduced tech in school, the students became more creative – they wanted to come up with more innovative projects.” His own students are banned from using phones at school, but he says they use them regularly at home to help with schoolwork.

Most education ministers have little say in their country’s infrastructure. But they can help EdTech developers to understand its limits. A national review of the digital infrastructure in schools would hand EdTech developers the blueprints to build better products. Such a review should look at how well schools are served by the basics: mains electricity and high-speed internet. It should also identify the types of technology most suited to the context of the learners and teachers. In some countries, for example, learners predominately use mobile phones over more laptops or tablets.

These insights can save both schools and developers a lot of time and wasted effort. In the long run, they can get products that work into schools – and also save an education system a lot of money.

A product may cost millions of dollars to create. To stand any hope of recuperating that investment, developers must sell at scale. In practice, many have to go from school to school, or district to district. Much of EdTech procurement is highly localised and fragmented across different regions. Deals are hammered out in individual schools, and profits made or lost in closely fought margins. This means that promising products can vanish from the markets before they ever get a chance to prove their worth at scale. One developer who spoke to the Atlantis Group said:

“For most EdTech companies it’s a massive struggle to succeed because it’s hard to make money. Selling to schools and governments around the world is incredibly hard and companies like me really struggle – so technologies die.”

Letting schools, or local authorities, pick and choose their technology helps to make sure that they are getting the products they need. But this approach is likely to limit learning about what works at scale. It also makes EdTech adoption across a system incredibly piecemeal. A minister of education may find that every school in their country has cobbled together a different set of technological solutions, all of which may or may not be compatible with others. As one Atlantis Group member – who also leads an EdTech company – reflected: “EdTech doesn’t exist as an industry; there are all kinds of initiatives that don’t know about each other.”

Fundamentally, EdTech should save teachers’ time – and governments’ money. Learning technologies, in other words, should be a cost-effective approach to service delivery. The reality is often very different. As one Atlantis Group member argued:

“When you think about the effect that technology has achieved in virtually every industry, cost savings are at the forefront. From healthcare to consumer products, technology has allowed users to be better served at lower costs. In education, the opposite is happening.”

Poor EdTech resourcing has arguably made education more expensive. It’s created new budget lines in education systems, and increased capital expenditures on hardware. Fundamentally, learning technologies should help governments to deliver educational services which, in their absence, would be impossible to afford.

All EdTech should pass the basic test of cost efficiency. In practice, this is easier said than done. At the national, regional and school levels, buyers often lack the basic information they need to weigh a product’s cost against its potential benefits. The problem is compounded at the policy level, as many governments still see learning technologies and other ICT as accessories to service delivery, rather than as essential components. The resulting situation has led one World Bank paper to, perhaps uncharitably, describe many investments in EdTech as “faith-based initiatives”.[8]

Education ministries have an important role to play in making EdTech procurement fair, transparent and cost-efficient. This doesn’t mean that policymakers should arbitrarily strip individual schools or districts of their power to buy the equipment they need. A one-size-fits all procurement solution would be ill-advised; as one expert who spoke to the Atlantis Group said:

“It’s incredibly difficult for any government agency to write a good procurement document – and very hard for a commercial organization to meet the needs of a good procurement document.”

The future may also see governments move away from one-size-fits all procurement solutions. Instead, a move towards micro-services and micro-procurement may give schools access to a far more flexible system of digital tools. In the meantime, ministers could look at facilitating opportunities for buyers and sellers to meet and do business more effectively. Buyers’ fairs, sponsored by regional education authorities, can help buyers and sellers alike – they give buyers a chance to sell at scale, and schools a vital opportunity to compare similar products. Ministers can also look to the example of countries like the UK, which is now trialling regional buying hubs and even pre-negotiated buying deals.[9] They could also examine the US, where the government has issued a number of procurement guidelines to assist developers and schools.[10]

Policymakers looking for more innovative or cost-saving models can also look further afield, to open-source solutions. Some countries such as India are already moving toward a set of open-source educational resources, on which private providers can build their solutions. Crucially, this means that data from these products are interoperable: they can be shared across different systems.

At the international level, there is also growing interest in EdTech created through open-source collaboration, where profit is not the principal motivator. The UNICEF Innovation Fund, for example, invests in open source solutions to improve the lives of children. Its portfolio includes a number of EdTech-based interventions.

More broadly, ministries should ensure procurement processes are focused on technology which promotes learning and teaching, rather than more generic hardware and software. Rather than measuring success by the number of computers or tablets in schools, policymakers should look at the learning technologies now available to teachers and learners.

Today’s EdTech can offer a set of learning interventions. It cannot yet provide the continuum of learning demanded by education systems at scale. That is something which only teachers can do. The demand for learning technologies from teachers, however, is often poorly understood by developers and policymakers alike. Both, as one expert put it to the Atlantis Group, tend to offer teachers solutions in search of problems.

Most teaching effectively happens behind closed doors. Teachers therefore have little incentive to use technology that they don’t want or don’t understand. Fundamentally, teachers must want to use technology because they believe that it will offer a more effective approach than what they are already doing. But few teachers seem to believe that they need more guidance around tech. In an OECD poll of teachers in 48 countries and economies, less than 20% of teachers said that they had a high need for professional development in ICT for teaching.[11]

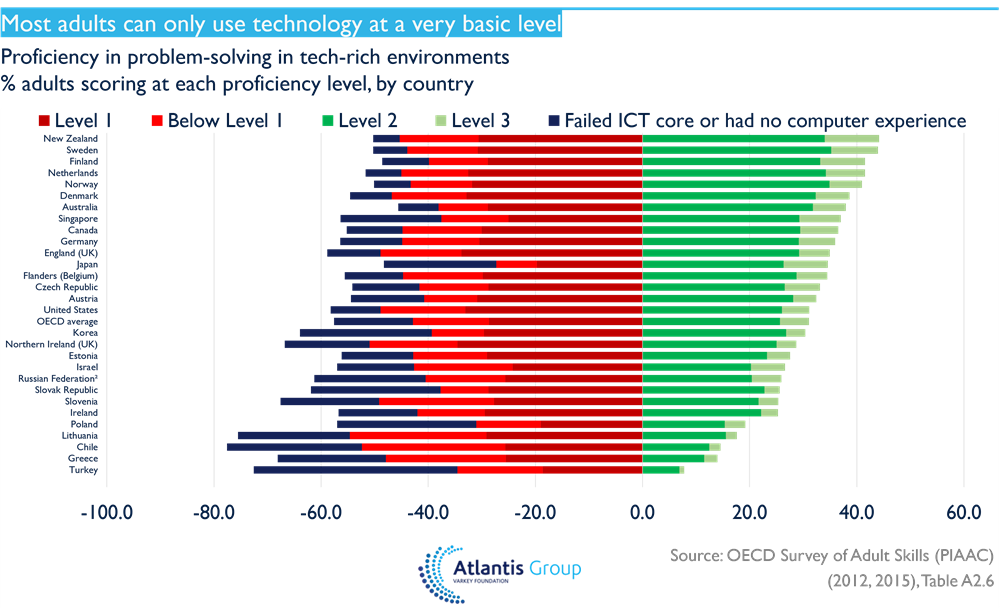

For governments to get teachers to adopt EdTech, they need to offer need two things. The first is adequate training into how to use the learning technologies effectively, including practical experience in the classroom. Training, where it does exist, is often divorced from pedagogy – from teaching and learning. Developers and policymakers alike should not overestimate teachers’ capacity to use ICT, beyond the most basic administrative tasks. Research by UNESCO, for example, shows that very few adults around the world can do more on the computer than copying and pasting files, or attaching files to emails.[12]

Some countries do offer teachers basic training in ICT, particularly during Initial Teacher Training programmes.[13] There is also evidence that a number of countries are beginning to prioritise in-classroom experience of such technology. Recent guidance from the US Department of Education, for example, recommends that pre-service teachers gain “program-deep and program-wide” experience with ICT.[14] The UK, meanwhile, has recently launched online training courses for leaders and education leaders.[15]

However, such training is neither widespread nor systematic in most education systems. Just 56% of teachers polled by the OECD reported that they had received formal training in ICT for teaching. In the US, widely seen as a global leader on EdTech, that figure is just 63%.[16] And where training is available, it is often an add-on or retrofit rather than an essential component.

As a result, educational technology may be too advanced for many users. As one Atlantis Group member noted: “We’ve heard time and time again that if you run ahead of the teaching profession it has a very negative impact on implementation of EdTech. The focus needs to be on training of teachers and drawing them in.”

The second thing ministers can do is to facilitate a process to give teachers a clear vision of how these products fit into the wider structure of learning that they are charged with delivering. The Atlantis Group has considered a range of different products over the course of its inquiry, each of which addressed a specific issue or provided teachers with a specific tool. But what contributors left unaddressed was how these products fit into the continuum of learning that teachers oversee. Practically, teachers need to understand how these different products are all supposed to work together in a classroom or school. They also need to understand how tech can enable their practice.

That is where education ministers can help. Fundamentally, teachers must see EdTech as more than the sum of its parts, rather than a collection of unconnected interventions. EdTech needs to be integrated with the curriculum, rather than as an add-on. As one Atlantis Group member said: “Teaching is not just a collection of tricks, it’s a structured thing. How does that structure fit in with EdTech?”

Teachers should also be able to rely on a network of support that extends beyond their school. Making EdTech a success takes many hands, from teachers and school leaders, to business and infrastructure, to civil society groups and local government.[17] Schools themselves are networked organizations with ties that extend far into their local communities. It takes an ecosystem of such stakeholders to build and sustain learning technologies, as well as to take them to scale. Teachers should not be asked to shoulder the responsibility of technology by themselves.

Governments should work to foster such local ecosystems. There is much that policymakers can do to help members of these communities to grow and learn from each other. A significant first step would be for education ministries to facilitate peer-to-peer learning opportunities for schools themselves, to help them to learn hard-won lessons about EdTech implementation.

EdTech is an uncharted frontier for policymakers, but it doesn’t have to be the Wild West. It’s the job of developers to push the boundaries of what is possible. But it’s the responsibility of ministers of education to realise EdTech’s full potential in the real world.

At a political level, that means addressing key issues around evidence, infrastructure, procurement and teaching and learning. But it should also mean articulating a clear political vision for EdTech. Too many policymakers treat technology largely as a supplement or retrofit to traditional education. Around the world, governments have focused largely on putting more and more hardware in classrooms, as well as digitizing their existing learning resources.

This approach has succeeded in putting more ICT in classrooms than ever before. But globally it has had resulted in only diminishing returns for learning. On average, 72% of students across OECD countries now say they use computers at school. But most report that they use them to browse the internet, rather than for practice or simulations.[18] Teachers and students, in other words, aren’t doing anything fundamentally different to before. As one expert who spoke to the Atlantis Group said: “In EdTech 1.0 we were digitizing traditional models – we just gave everyone a computer. Nothing has really changed, we’ve just added tech, overlaid over the existing framework.”

This is an enormous waste of time and resources. To realise EdTech’s promise, policymakers need a clear strategy for ICT and how it serves learning throughout the system. In practice, however, such visions are few and far between. A World Bank review of ICT policymaking for education around the world has concluded that very few countries have working EdTech strategies. Many have no EdTech strategy at all. Others have policies cobbled together from the disparate strategies of different sectors, or strategies working in practice which have never been officially adopted.[19]

It’s time to break the cycle of political failure around EdTech. Ministers of education should consider examples of best practice where they do exist, notably in Singapore, the UK and the US.[20] They may also ask themselves searching questions about what’s working, and what’s not. Fundamentally, education ministries must be prepared to see EdTech as more than a supplement to traditional education. Instead, they must work to identify the most effective technology, and integrate it gradually into day-to-day classroom practice. To accomplish that, education leaders can look to the next wave of educational technology: EdTech 2.0.

Notes

[1] Pilar Cuesta, Maria; Mingo, Florencia; Zacharias, Sharon. What are the most promising areas of technology initiatives in education? How can governments in low and middle-income countries in Latin America and Sub-Saharan Africa support these? Graduate School of Education, Harvard University and the Varkey Foundation (2018; paper available on request.)

[2] For a summary see eg, “Technological interventions increase learning—but only if they enhance the teacher learner relationship”, World Development Report 2018: Learning to Realize Education’s Promise, World Bank (2018), pp145-147. Citing data and analysis from Muralidharan, Singh, and Ganimian (2016, Appendix B).

[3] Students, Computers and Learning: Making the Connection, PISA, OECD Publishing, Paris (2015)

[4] Trucano, M., SABER-ICT Framework Paper for Policy Analysis: Documenting national educational technology policies around the world and their evolution over time. World Bank Education, Technology & Innovation: SABER-ICT Technical Paper Series (#01). The World Bank (2016)

[5] “Technological interventions increase learning—but only if they enhance the teacher learner relationship”, World Development Report 2018: Learning to Realize Education’s Promise, World Bank (2018), p145-147

[6] Scaling Access & Impact: Realizing the Power of EdTech, Omidyar Network (2019)

[7] Electricity and education: The benefits, barriers, and recommendations for achieving the electrification of primary and secondary schools, UNDESA (2014), citing UNESCO UIS.

[8] Trucano, M., SABER-ICT Framework Paper for Policy Analysis: Documenting national educational technology policies around the world and their evolution over time. World Bank Education, Technology & Innovation: SABER-ICT Technical Paper Series (#01). The World Bank (2016)

[9] Realising the potential of technology in education: A strategy for education providers and the technology industry, Department for Education (2019)

[10] See, eg, Ed Tech Developer’s Guide, US Department of Education (2015)

[11] Figure I.1.1, TALIS 2018 Results (Volume I): Teachers and school leaders as lifelong learners (OECD), 2019

[12] “Target 4.4: Skills for work”, http://gem-report-2019.unesco.org [accessed 24 May 2019]

[13] Trucano, M., SABER-ICT Framework Paper for Policy Analysis: Documenting national educational technology policies around the world and their evolution over time. World Bank Education, Technology & Innovation: SABER-ICT Technical Paper Series (#01). The World Bank (2016)

[14] “Advancing educational technology in teacher preparation: Four guiding principles”, Reimagining the Role of Technology in Education: 2017 National Education Technology Plan Update, Department of Education (US)

[15] Realising the potential of technology in education: A strategy for education providers and the technology industry, Department for Education (UK)

[16] Figure I.1.1, TALIS 2018 Results (Volume I): Teachers and school leaders as lifelong learners (OECD), 2019

[17] Scaling Access & Impact: Realizing the Power of EdTech, Omidyar Network (2019)

[18] Students, Computers and Learning: Making the Connection, PISA, OECD Publishing, Paris (2015)

[19] Trucano, M., SABER-ICT Framework Paper for Policy Analysis: Documenting national educational technology policies around the world and their evolution over time. World Bank Education, Technology & Innovation: SABER-ICT Technical Paper Series (#01). The World Bank (2016)

[20] See eg ICT Masterplans (Singapore), Realising the potential of technology in education: A strategy for education providers and the technology industry (UK) and National Education Technology Plan (US)